Molecular structures are traditionally described with Schoenflies notation but this approach was intended to describe the external morphology of crystals. It is an ad-hoc system derived by various researchers during the 19th century and published in its final form in 1891, a quarter of a century before the advent of simple models of the atom. It does not work very well when applied to molecular structure because it was never intended for that purpose. Its use in molecular work demands pages of calculations to produce results that can be deduced by inspection - the easy way.

Point groups in Laue classes

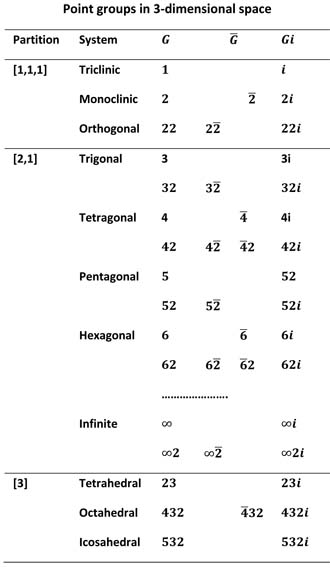

Molecular symmetry is described by an infinite number of three dimensional point groups shown in the table on the right. Each point group in the table belongs to a spatial partition and within this division to a system based on the main axial order of the group. Systems themselves are divided into one or two rows of Laue classes based on the rotational group G in the leftmost column of the table. Rotational groups in the [1,1,1] and [2,1] partitions are either cyclic groups n or dihedral groups n2, using notation similar to that of Hermann-Mauguin, in which the first figure is the main rotational order and the second a 2-fold rotation at right angles to the first axis. Point groups in partition [3] have spatial transformations in three dimensions, requiring three rotatitonal orders that are not mutually at right angles.

Rotational groups

Non-rotational point groups in Laue classes

Each Laue class contains a set of 2,3 or 4 point groups defined by the rotational group G in the first column. Each class must also contain a group Gi that is simply the direct product of the rotational group for that class with space inversion (parity inversion). It is of twice the order of the rotational group and contains the space inversion operation itself. In addition to these two groups a Laue class might also contain one or two semi-direct product groups that formed by combining one of the rotational group generators with space inversion. A cyclic group only has one generator so only one semi-direct group can be formed from it but a dihedral group is able to form two non-rotational groups in this way. The inverted generator is distinguished with an over-bar. Groups of this kind have exactly the same abstract algebraic structure as the rotational group because inversion does not change the rotational component of the multiplication product. Semi-direct product groups do not contain the spatial inversion element itself but direct product groups do. Obviously all groups in a Laue class have the same number of elements (the order) except for the direct product group Gi which has twice as many as the other groups. The tetrahedral and octahedral Laue classes are related in a similar way to that of the cyclic and dihedral groups in the less symmetric partitions. All octahedral groups have an index-2 tetrahedral subgroup that provides an underlying symmetry.

Non-rotational groups

Irreducible representations

Symmetry operations in a three dimensional space can be described by matrices showing how atoms are pernmuted during the operation. Permutation representations produced in this way can always be reduced to a number of 1 dimensional irreducible representation (irreps) in the [1,1,1] partition, to a mixture of 1 and 2 dimensional irreps in the [2,1] partition, goling up to 3 dimensions in the [3] partition.

Groups in a Laue class have the same irreps because they are distinct manifestations of the same abstract group on which the irreps depend. Direct-product (centred) groups are direct products of the defining rotational group (or any other group in the class) and spatial inverson. their irreps are simple direct products of rotational group irreps and the spatial inversion irreps. A number of simple rules can be used to deduce molecular irreps - the byzantine calculations contained in some text books are just not necessary

Irrreducible representations

Relativistic (Double) point groups

All of the reasoning above relates to objects moving in a three dimensional space and has been found to work very well when applied to the electronic, vibrational and rotational motions in atoms and molecules. Unfortunately, as atoms become more massive in the middle of the periodic table, electrons are drawn into the nucleus and travel much faster. Electrons in heavy atoms can travel at two-thirds of the speed of light, a speed at which special relativity becomes significant. Double point groups describe atomic structure in four dimensional space time but theikr arrangement in Laue classes with spatial inversion makes their treatment straightforward.

Atomic orbitals

Treatments of atomic orbitals in three dimensions invariably rest on solutions to the 3D wave equation developed by Schrodinger. Extensions to 4D space-time use the Dirac equation. In both cases the equations produce pure one-electron orbital solutions that then act as bases for many-electron treatments. Simple crystal field theory can be applied to such orbitals to give a surprisingly good picture of how atomic energy levels may change in different environments.

Molecular orbitals

Electrons are disposed about a nucleus at distances and angles explained by the Schrodinger equation as orbitals surrounding the nucleus. Atoms combine to form molecules when these atomic orbitals combine to form molecular orbitals. Atomic orbital symmetry dictates the allowed molecular symmetries when these combinations occur. Transitions of electrons between the different energy levels of molecular orbitals is also dependent on molecular synmmetry

Molecular vibration

Molecules are considered to be semi-rigid so that atoms within them are able to stretch, contract and bend about an equilibrium position. The wave nature of vibrational motion can be treated as the motion of an harmonic oscillator and the energies of the allowed levels revealed by the Schrodinger equation. Allowed levels, which can be quite complex, are then labelled by the irreducible representations of the molecular point group

Molecular rotation

Molecular rotations depend on the moments of inertia in the molecule. In this context, chemists usually describe the [1, 1, 1], [2, 1] and [3] partitions as asymmetric, symmetric and spherical molecules, having respectively 3, 2 and 1 distinct moments of inertia. Again the Schrodinger equation is applied and rotational energy levels are obtained from the moments of inertia. It is difficult apply the equation to asymmetric molecules because of the three different inertias but quite simple to apply it to spherical molecules Rotational spectra are useful to probe mass and dimension within molecules but are not directly related to point groups.

Click on a row for more information on groups in that Laue class

Images of molecules belonging to each clasess allow the various operations to be pictured.

The table above shows the three partions of a three dimensional space labelled [1, 1, 1], [2, 1] and [3] and the sub-divisions of these partitions into systems and Laue classes. Chemists usually describe this as a division between asymmetric, symmetric and spherical molecules. While the [1. 1. 1] and [3] partitions contain just three Laue classes there is an infinite number of such classes in the [2, 1] partition.

The first column contains purely rotational point groups, the second and third contain semi-direct products of rotational groups with space inversion while the final column contains point groups that are direct products of the rotational groups for the class with space inversion. Laue classes in the [1, 1, 1] and [2, 1] partitions consist of an infinite series of cyclic groups n that describe molecules of n-fold symmetry and dihedral groups n2 that describe the same n-fold symmetry accompanied by a 2-fold rotation about an axis at right angles to the n-fold axis. Classes in the [3] partition have rotational symmetry axes that are not necessarily aligned with the Cartesian axes although most symmetry operations may be pictured in this way. Each number in the notation may be seen as a "generator" so that, for example, symbol 6 represents a 360/6 degree rotation (around the z axis) and 6 applications of the generator return the molecule to its original position. Symbol 2 in the second position represents a 2-fold rotation about the y axis in dihedral groups. Rotational group symbols written is this way are are very similar to those of the Hermann-Mauguin (International) system used in crystallography. However, the international system is unecessarily complicated for molecular work because it has to describe each of the 230 three dimensional space groups.

Crystallographic point group symbols rely heavily on mirror reflections combined with spatial movement to produce "glide planes" in crystal symmetry. Instead of simply considering centrosymmetric groups as direct products of a group G with inversion i (G x i) crystallographers use a mass of reflections that are later combined with spatial translations. Atomic and molecular work is more concerned with the algebraic structure of the point group in which reflections are something of a nuisance. This happens because the reflection operation (m) does not generally commute with rotational operations so gm and mg produce different results. Inversion on the other hand always produces the same result regardless of the order in which operatins are applied because it commutes with all other operations.

A Laue class contains a rotational group, 0, 1 or 2 semi-direct product groups and a centred group. Each of the semi-direct product groups combines one generator of the corresponding rotational group with spatial inversion. Since spatial inversion does not alter the order in which rotational elements combine each semi-direct product group has the same abstract structure as the rotational group. In effect, all groups in a Laue class are distinct manifestations of the same abstract group. Describing point groups in this way makes computation much simpler.

Schoenflies notation was replaced in crystallographic use following the introduction of the Hermann-Mauguin (International) system in 1931. This allowed each of the 230/219 three dimensional space groups to be described directly but provided no advantage for molecular work where point groups are sufficient. Although Hermann-Mauguin notation appears to use lot of reflections the fact that it fits into a structure of systems and Laue classes are defined by crysallographers as collections of point groups that show the same centred group in X-ray diffraction.

Symmetry and point group references

There exists an enormous volume of literature on symmetry groups and their applications in crystallography and molecular work.

The scheme presented here was derived as part of a system to describe point groups in higher dimensional spaces in which the 2-fold dihedral operation was given label u. Later work revealed the advantages of this system for molecular point group applications in three dimensions. Replacing the letter u by the number 2 allows this system to appear quite similar to the three dimensional international notation, particularly for the rotational groups and there is no ambiguity in three dimensions.